JUDGES EDUCATION

Scottish Terrier Club of America provides educational opportunities for individuals seeking American Kennel Club approval to judge the Scottish Terrier breed. The purpose of this committee is to present Scottish Terrier Breed Seminars and other educational forms that may fulfill this duty throughout the United States. Breeders, exhibitors, and interested persons are encouraged to attend and participate as well as to those seeking judging approval.

Educational Reference and Articles on the Scottish Terrier:

What Color is a Scottish Terrier?

For the novice and the unfamiliar the color black might be an answer. Longtime breeders and knowledgeable terrier judges are well aware that the breed has a coat of many colors, textures and shades. Although this article focuses upon and presents illustrations of some of these colors it is critical to the understanding of the Scottish Terrier that the coat not the color is of greater importance.

Historically the Scot has always been a multi-colored breed. Mackie in the early 1880’s visited the highlands to view and record information about Scottish Terriers. It was and is still a purposeful breed and each regional gamekeeper selected and bred dogs for their gameness and ability to rid the area of vermin. Captain Mackie recorded dogs of many colors; red, brindle, fawn, grizzly, black, and sandy. The reports described coats “as hard as any would want” and specifically “rough-coated”. By the year 1880 a committee formed to describe the breed characteristics and the only mention of color was, “white marking objectionable”. The first English Standard (1887) was more detailed and identified a variety of shades of Scottish Terrier as, “Steel or iron grey, black brindle, brown brindle, grey brindle, black, sandy and wheaten. White markings are objectionable and can only be allowed on the chest and to a small extent.” The American Standard (1947) continued to recognize coat color as “steel or iron grey, brindle or grizzled, black sandy or wheaten.” In 1993 the color was changed dropping the grizzle and changing to Black, Wheaten or Brindle of any color. However it is critical that the original colors identified in the earlier standard not be penalized in anyway and that colors, although rarer today, still may and do occur and are acceptable.

Recently, there have been situations in several breeds with unlisted and unacceptable colors being shown. The AKC and affected breed clubs have advised judges to penalize accordingly or excuse for lack of merit. Long-time breeders and judges of the Scottish Terrier are cognizant that our beloved breed has many coat colors. Our Scottish Terriers are still producing the colors described in the breed history and these should not be faulted or penalized.

While this article presents the phonotypical manifestations within the Scottish Terrier it should be noted that genotypically there are many combinations that can and do occur. The basic understanding of dominant and recessive genes is far too simple in predicating the coat color in the Scottish Terrier. Color is polygenic and Little in his “The Inheritance of Coat Color in Dogs” suggests nine genes that can combine and influence its expression within the breed. A visibly black appearing dog may breed as a true black and produce black pups or in fact my produce brindle offspring as a result of carrying a brindle allele. The Scottish Terrier can be solid or brindled, darker or lighter, black, sandy, red, rich reddish wheaten or paler. It can have a dark mask visible on the brindles (although the solid black may also have a mask it is indistinguishable on the dog), brindles may appear in varying depths of color and shades (red, silver, brown, etc.). Wheaten can appear in any variation from cream through deeper red. Shading on the wheaten is very common as the length and age of the stripped coat and undercoat may influence the color. Even a black dog is not just black but occurs in many tones and shades. White is still allowable to a slight extent on the chest and on the chin which breeders refer to as a milk beard. Upon closer examination of these areas one will find that the white is often a dilute brindle. Often a few white hairs may be found on the body coat with no penalty. Some owners will pluck these and others will leave them as evidence that the dog was not artificially colored for the discerning judge. Infrequently black and tan markings have been known to occur in the breed. Solid reds and sandies are rare but permissible.

The color descriptions and pictures illustrate the variety that may be seen in the Scottish Terrier and are glorious in their variety.

Which color is preferred? No color is preferred over another! An examination of the suggested scale of points clearly conveys the percentage valuing of color in the Scottish Terrier as ZERO. The coat itself however is a salient feature of the breed. Look for, value and reward the Scot that carries the double coat that insulates his sturdy body. Feel the soft dense undercoat and rub the topcoat between your fingers determining its hard, wiry, weather resistant texture essential for the dog’s original purpose. Now reward the coat not the color. The Scottish Terrier is one of the most instantaneously recognized silhouettes, but the dog himself is much more than a cutout or licorice flavored dog candy. It may be easier to see the outline on a solid dog. The lighter shades may appear larger. Breeders and judges both should select the best Scottish Terrier. Any selective breeding that focuses upon a characteristic over time may produce the desired traits. Color alone is far too simple and may be to the detriment of selecting the best dog and breeding for other critical components. We all need to choose the best dog of ANY color.

Scottie Character and Sparring by Kathleen Ferris

Published 8/2014 in the AKC Gazette

“NO JUDGE SHOULD PUT TO WINNERS OR BEST OF BREED ANY SCOTTISH TERRIER NOT SHOWING REAL TERRIER CHARACTER IN THE RING” A key phrase from our standard.

This is a key phrase from our standard. It should be pretty self-explanatory -but is it? I am approached many times to explain or clarify this and it always leads to discussion of “Sparring.” Those who have grown up with Scotties know that sparring is just one way to show Terrier character in the ring. However I seem to hear that there needs to be better education on how to spar, when to do it and is it the only way to show that character.

What is sparring? Webster’s says, “to gesture without landing a blow…” I love this description. When I started it was commonplace to see terriers sparred. Dogs were brought out to face off and display their alert attitude. Judges brought 2 dogs but rarely more than 3 center ring. Tails would become rigid, ears erect and occasionally a quivery lip would show a hint of tooth. Never contact. Not to say that occasionally a tuft of beard might end up in the air. But that was greatly discouraged. The best dogs never left the ground. They just drew a line in the grass and said I dare you, simply a glorious stare down.

Sadly I hear stories of bad sparring. Concerns are how a judge allows it, how an exhibitor controls their dog and what spectators see in the ring. Perhaps some helpful advice is in order since I would hate to see this practice disappear.

As an exhibitor always have your dog in control in the ring. Train your terrier not fly into the air in a rage but rather stand its ground. Know the distance you can approach another terrier before your dog reacts. Ring awareness of your surroundings, fellow exhibitors and their dogs is a must. When asked to spar, listen to directions. If none, take the lead and control the situation by how close you allow your dog to get. All the judge needs to see is your dog’s positive attitude. If asked to get closer stay your ground.

Judges you are in control of your ring. If you choose to spar terriers then make sure you know how. If not, consider whether or not you should do it. Go to people you respect in breeds that spar. Get feedback on what is correct and/or safe. Watch it being done before you give it a go. My general rule of thumb is never spar more than 2 dogs. Bring them center ring with lots of space around. State clearly that you just want them to look and you do not want contact or see them leave the ground. If attitude is there it will be displayed immediately. If it is not, do not push the issue. If the exhibitors start to get too close tell them to back away. Never allow the dogs to connect. We do not want to see dogs injured and we need to think how it would appear to spectators. We do not want any thought that you are encouraging dog fighting. That will only do all of us and our sport a disservice. Once you see that bristly attitude dismiss the dogs back into position. Please never spar a puppy with an adult. It is too great a risk for a young temperament.

As for “real terrier character” sparring is not the only test. Look for an attitude of confidence, a firm stance for examination, a head and tails up movement in a group going around or a solo down and back. It is a dog that comes back to a judge with an air of superiority that says look at me.

Ultimately we all have to choose our way to evaluate this. Sparring is simply one option and when done poorly the repercussions are not worth the risk. However correctly managed it is a beautiful sight. Two specimens at the end of their leads standing their ground telling each other and the world this is their turf and no one else’s.

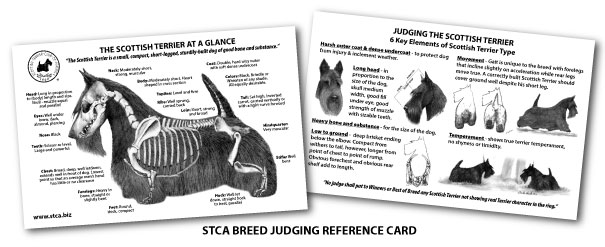

Author’s Note: The diagrams and pictures used in this article have been copied from their original sources as they appeared. The skeleton picture (with double shoulders) and the final picture in the article were modified for their purpose. I must extend my unending gratitude to Darle Heck who, when asked, provided the lines and rulers on the pictures making my simple line drawings much more attractive and informative. This article originated from my investigations and viewpoint; it does not necessarily represent the views of the members of the STCA Standard Review Committee.

“Lovely Fire” By Mrs. Evelyn Kirk

Article written by Breeder Judge Mrs. Evelyn Kirk, Balachan Scotties in 1977.

Reprinted with permission of Laura Kirk Zimmerman

About six years ago, when asked about it, Tony Stamm agreed that “Type, like beauty, lies in the eyes of the beholder.” I think to a great extent that is true. I’ve been present (on the other end of the lead) when a judge said, “This is a close decision: the two dogs are so much alike,” when I thought they were like night and day. Also, the other extreme, “These two dogs are very different, each good in his own way,” when I thought them almost identical.

But, what makes the dog typical, what sets him apart from all the other animals in the world? I believe it’s his pride in being a Scottish Terrier!

His commanding presence, his unflinching gaze, and his deep rooted conviction that he is his own man; these are the attributes of the adult Scottish Terrier of a proper type. Once witnessed, this attitude is hard to forget. Seldom seen, it is a thrilling experience.

I don’t want to mislead you; the dog must have all the other features which label him a Scottie, even to the untrained eye. The inexperienced spectator can pick the right dog almost every time because he dog is so pleasing to behold.

This is where good balance comes in. The dog must not look as if he is going to tip over on his nose. In outline, he must have that beautiful line down his arched neck, over his well-knit withers, and onto his rather short back to his handful of tail. It’s a pleasure to run your hands over such a dog. It should be a continuous flow, not interrupted at the withers by too-straight shoulders or a roach over loin.

There should be enough of him extending behind his tail to balance his forepiece. Well-muscled thighs fill your hands and you think to yourself, “Good Hams.” You’d like to give that broad bottom a pat, but you feel the impropriety of such a gesture. The feet are firmly planted and the upright hocks unyielding to pressure.

His brisket is deep, deep and well-padded with flesh to protect the point of ribs when he is hard at work. It is on this pad that his body rests, freeing his forelegs to dig. A round rib cage is a detriment to a typical Scottish Terrier. The rib cage extends well back so that his last rib is definitely beyond the halfway point on his body.

The forelegs do not come down straight from the point of shoulder on the typical Scottish Terrier. They extend down from his elbow, which is at the end of his upper arm. This upper arm, often overlooked, is an essential part of his front assembly. The proper length of upper arm allows the dog’s forelegs to be set well back at his sides, displaying his broad chest and providing the room needed for his deep brisket between those legs. His proper lay-back of shoulder blade will give him the reach needed to offset the thrust of his powerful hindquarters.

The beauty of his head can be enhanced by proper grooming. Whiskers combed forward, the head is a rectangle. Lean at the sides of the skull, it diminishes very little to the muzzle. It is filled in under the eyes in the molar area of the upper jaw.

His large black nose twitches with interest as you approach and he allows you to examine his wide, scissor bite. His head is heavy in your hands and you can hardly encircle his muzzle with your fingers. His deep-set eyes have a dark expression of composure and something else, not definable.

Overall, there stretches a tight jacket of various textures. Softest of all is on his small ears. The rest of his hair is hard with his back coat being of great coarseness. As you test his coat in a scratching motion, your fingertips come in contact with and undercoat of incredible thick down.

As the dog is placed on the floor to exhibit that gait which is peculiarly his own, he invariably shakes. He must get comfortable again, after being lifted onto and off the table and after you have touched him and disarranged his hair. He gives you a quick disdainful glance as he moves off about his business.

You wonder, as you watch him gait, pose and stalk past his competitors, how could so much dog be packed inside that small package? Where did he get that indomitable spirit; from whom did he acquire that unshakable faith in himself?

Without this temperament, the “Lovely Fire,” as Heywood Hartley expresses it, the dog is just another dog. The “cutey-pies” that wag, and kiss, and wiggle their way into your heart, makes friends for the breed and we thank God for them, but the dog that makes you spine tingle, that makes a lump come into your throat, who stands alone in his undeniable glory is the typical SCOTTISH TERRIER.

Educational Events on the Scottish Terrier:

Presented on May 8, 2020

STCA Judges’ Education Coordinator:

Contact the STCA Judges’ Education Coordinators for information regarding presentations on the Scottish Terrier and/or to schedule a ringside observation

Candidates to judge the Scottish Terrier are strongly encouraged to observe the breed during major entries at the National and/or Regional Specialties. Observers should attempt to observe with a variety of mentors and follow the rules for observations on the AKC website. All prospective judges are strongly encouraged to obtain “The Illustrated Guide to the Scottish Terrier” c2010 from the STCA.

STCA Approved Breed Mentors:

All judges’ mentors that meet the STCA Requirements of 15 years experience in Scottish Terriers and have groomed, conditioned and successfully handled 15 dogs to championship status. In addition their dogs have been Winners or better at (2) regional or national specialties. These mentors have been approved by the STCA Board of Directors. These individuals are available in regions of the United States and are generally available for assistance and ringside mentoring. In addition to these judges mentors may observe with other individuals that meet the AKC criteria including approved judges with regular status judging the breed for over 12 years.